Runaway Jury

for violence, language and thematic elements.

for violence, language and thematic elements.

Reviewed by: Kenneth R. Morefield, Ph.D.

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Crime Drama Thriller |

| Length: | 2 hr. 7 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2003 |

| USA Release: |

October 17, 2003 |

| Featuring |

John Cusack Gene Hackman Dustin Hoffman Rachel Weisz John Cusack Jennifer Beals Marguerite Moreau Celia Weston Cliff Curtis Bruce McGill Joanna Going Jeremy Piven Nick Searcy Luis Guzmán Dylan McDermott Bruce Davison Orlando Jones Nora Dunn |

| Director |

Gary Fleder |

| Producer |

Arnon Milchan John Grisham Christopher Mankiewicz Gary Fleder |

| Distributor |

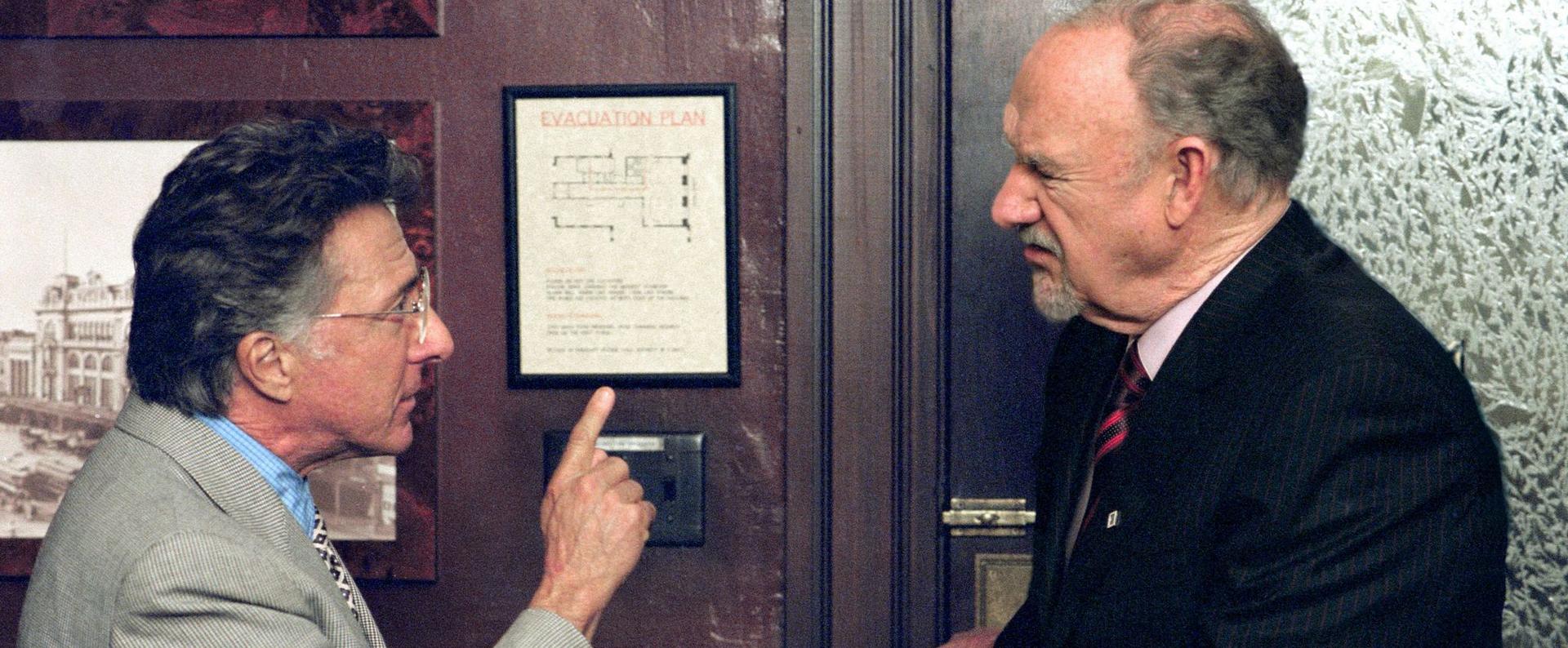

Nicholas Easter (John Cusack) and his partner, Marlee (Rachel Weisz) try to manipulate the jury of a civil suit against a gun manufacturer. Gene Hackman plays a jury consultant for the gun company and Dustin Hoffman plays the lawyer for the plaintiff. Each must decide whether or not to accept Marlee’s offer to fix the outcome of the trial in exchange for ten million dollars. WARNING: SOME PLOT SPOILERS IN THIS REVIEW!

A case could be made that John Grisham was the most successful Christian author of fiction in the twentieth-century. Part of his success, however, is no doubt tied to that fact that his fiction (other than The Testament) tends to eschew overtly Christian topics and overtly Christian characters. I was not even aware that Grisham was a professing Baptist Christian until, after reading The Testament, I researched his biography. Given the fact that he writes about his profession more than his professions, is it even relevant in a film or book review to mention that Grisham is a Christian? Is it meaningful to call him a Christian writer? I think it is.

Grisham has made it clear that his faith informs his writing even if it isn’t the subject of his writing. For example, he mentioned in a speech at Baylor University that his stance on the death penalty is based primarily on his answer to the question of whether or not it is consistent with Jesus’s teachings.

“Runaway Jury” is a briskly moving suspense-mystery that will probably win more Christian fans for its lack of sex, nudity, or heavy profanity than it will for its subject matter. Indeed, one of the more curious elements of the film is that it is even more sanctimonious than the novel upon which it is based.

In the book, the lawsuit is against a tobacco company rather than a gun company, and while the change makes the plot a bit more topical it also complicates the our relationship to the protagonists and their motivation. American audiences, not just those of Christian persuasion, like their heroes and villains defined unambiguously, so it seems obvious that the largest reason for the changes is to increase the culpability of the defense in general and of Hackman’s character, Rankin Fitch, in particular.

Witness the scene in which Hoffman’s character confronts Fitch in the bathroom of the courthouse and Fitch blithely declares regarding both the rule of law and the people whose lives have been destroyed by his client: “I don’t give a s***.” It is easier for us to accept the fact that the intended heroes are basically doing everything they are condemning—Fitch’s character for practicing (subverting the jury process, blackmailing those they disagree with, lying under oath)—if we are constantly reminded that their reasons for doing so are defensible while his reasons are self-serving. Easter and Marlee extort fifteen million dollars, but it isn’t for them. He did not persuade the jury to vote the way he wanted, Easter insists (though if he did he would be right to do so, the movie hedges), he merely freed them to vote their hearts by protecting them from Fitch’s unjust and unfair influence.

This self-justification, which the movie accepts as legitimate, is at odds with Easter’s actions in deliberation. He does persuade the jury (though only after he gets a message that the bribe money has been safely transferred) and he does so rather disingenuously, couching what is essentially an emotional appeal in language that insists without evidence, that the law is on his side.

I am not claiming that the gun company would or should win such a case, just that Easter and the film beg the question completely by refusing to present an affirmative argument that the case would or should be won if not for Fitch’s interference. No matter how slimy the film makes Fitch, it can’t hide the fact that Easter’s and Marlee’s argument is an essentially non-Christian (and I would argue un-American) one: the ends justify the means.

Ultimately, however, the makers of the film bank on the fact that the audience will share enough of the frustration of the characters at seeing justice denied or perverted by the rich and powerful, that they will be happy to let Fitch be a scapegoat even if Easter has to sully his conscience to get him, and they may be right.

The film tries to recapture some of the moral high ground for the prosecution by having Hoffman’s character (Wendell Rohr) refuse to buy the verdict even though he believes this principle will cost him and his client dearly. His idealism, however, is presented as misguided and impotent. Rohr wins the case, the film argues, not because his faith in doing right is well founded, but because someone like Easter is willing to do what Rohr’s conscience won’t allow. Vengeance may not be Rohr’s, but it isn’t exactly left for the Lord, either.

This double-mindedness may not keep Christians from enjoying the film as an entertainment piece, but it may prevent the more serious thinkers among them from truly embracing it. Unlike “The Firm”, in which the protagonist finds his salvation by returning to the law that he had previously abandoned, “Runaway Jury” doesn’t even know its protagonist is lost.

My Grade: B+ | Violence: Mild | Profanity: Minor | Sex/Nudity: None

[Better than Average/3]

[3 ]

[Better than Average/2]

What the secular world refused to recognize as the root cause in the Columbine tragedy is the fact that kids are taught that they are merely animals within a long chain of millions of years of death, tooth and claw evolution—why are we then surprised when they behave like animals? (Harris and Kliebold were both strong believers and proselytizers in the theory of evolution—Harris died wearing a shirt that read “natural selection”).

As I watched this movie, the verse that kept popping into my head was Isaiah 5:20 “Woe to those who call evil good, and good evil.” Extortionist anti-gun activists and sympathetic liberal lawyers are painted as good, while the 2nd amendment and the Biblical principle allowing us the right to defend ourselves is painted as evil (albeit indirectly).

[Average/2]

My Ratings: [Average/4]