Waiting for Superman

for some thematic material, mild language and incidental smoking.

for some thematic material, mild language and incidental smoking.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Good |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults Family |

| Genre: | Documentary |

| Length: | 1 hr. 42 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2010 |

| USA Release: |

January 22, 2010 (festival) October 8, 2010 (wide) DVD: February 8, 2011 |

Why is there a disconnect between Hollywood and the rest of America? Answer

SECULAR HUMANISM—Is the religion of Secular Humanism being taught in public school classrooms? Answer

MORALITY—Are we living in a moral Stone Age? Answer

SCHOOL VIOLENCE—what’s the answer? Answer

EVOLUTIONIST TEACHERS—10 TIPS for Christian students in secular classrooms

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM—What is legally permissible for students in America’s public schools? Answer

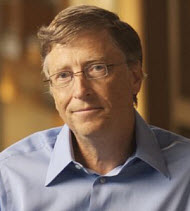

| Featuring | The Black Family (Themselves), Geoffrey Canada (Himself), The Esparza Family (Themselves), The Hill Family (Themselves), George Reeves (Superman), Michelle Rhee (Herself), Bill Strickland (Himself), Randi Weingarten (Herself) |

| Director | Davis Guggenheim—“An Inconvenient Truth” |

| Producer | Electric Kinney Films, Participant Media, Walden Media, Michael Birtel, Lesley Chilcott, Eliza Hindmarch, Michelle Katz, Jeff Skoll, Shari Tavey, Diane Weyermann |

| Distributor | Paramount Vantage |

“The fate of our country won’t be decided on a battlefield, it will be determined in a classroom.”

I approached Davis Guggenheim’s documentary, “Waiting for Superman,” with some trepidation. I couldn’t sit through his last documentary, “An Inconvenient Truth,” a visually enhanced lecture that went beyond political argument, and even evangelism, into the realm of propagation of faith doctrine. “…Truth…” is a video bible for elites. It lays down a religion—and a religion it certainly is—that has a god (Mother Earth), a venerable saint (Al Gore), and forces of good and evil. Who is the leader of the good forces? That would be Gore, again. And the bad guys? Anyone, even a scientist, who might dare to raise a question about the film’s premise. Believers are anointed ones; dissenters are heretics.

“Waiting for Superman” takes the same approach as “…Truth…”; Guggenheim throws a lot of statistics at us, and he puts up a lot of graphs. Sometimes, I felt as though I was back in school, attending another dry social studies class. A series of moving cartoons made it a little more interesting than lectures I remember, but a lot of that data still buzzes past me. Yet, it did not take long for the film to take hold. Actually, Guggenheim had me in the first few minutes. He begins his narration as he drives his own children to school in Los Angeles. In order to get them there, he has to pass several neighborhood schools, all of which have fallen into states of disrepair and have awful scholastic records. He admits that he, by virtue of his financial and social standing, is able to pass each of these broken down schools and bring his own children to an expensive private institution that is beyond the financial reach of most families. He seems to acknowledge that he has the means to shelter his own children from the very system that Hollywood elite society, of which he is a member, has always championed in its films and in its political activism. That opening segment reveals how elites do not have to live with the consequences of a lot of the ideas and the values they promote.

Why is there a disconnect between Hollywood and the rest of America? Answer

“Waiting for Superman” (the title refers to the everyday characters in the comic book serial who are in desperate straits from which only a super hero can save them) may not be an eye opener; it contains data we intuitively know to be true, but Guggenheim has put it into a context that makes us feel it and want to do something about it. He introduces us to people who are trying to do something, and those few are the heroes of the film. Their stories, and the stories of the children who depend on those solution seekers, are the heart of this exceptional movie.

The film focuses on the lives of five students. Daisy is a fifth grader who lives in a poor area of Los Angeles. She lives with her working mother and her unemployed father. Her chances of performing well enough to go on to a good middle school, a good high school, and a good college, where she can pursue her dream of being a doctor or a veterinarian are slim, if she remains a student at the bad inner city grade school she now attends.

Francisco is a first grader who lives in the Bronx with his mother and attends a poorly performing school. His mother makes numerous attempts to meet with his teacher to discuss Francisco’s lagging performance, but the teacher does not respond.

Anthony is a fifth grader who struggles in a Washington, D.C. grade school. He lives with his grandparents, after his father died from a drug overdose, and, without a decent education, he is at risk of meeting a similar fate.

Bianca is a kindergarten student who lives in Harlem. Her single mother works extra shifts in order to afford tuition to send her daughter to a private school.

Emily is a middle class 8th grader who lives with her parents in Silicon Valley and attends a comfortable school that has a lush green campus, an array of modern technological equipment, and a state of the art gymnasium. But Emily is underperforming and falling through the cracks. She is somewhere between the best and brightest who are being groomed for placement at top state universities and those at the bottom of the class who will most likely go on to trade jobs after high school. Her parents want to send her to a less prestigious, but better performing charter school in another part of town.

All these students are different; that’s part of what makes each one so fascinating; yet they all have something in common. They want a better education and are willing to do what they have to do to get it. They face what seem to be insurmountable odds. They did not choose their lot. The schools they attend were chosen for them, by a system whose admission guidelines are based on geography and financial status. The only chance they have to avoid attending an inner city school and almost certain failure, is to take part in a lottery that picks a few lucky students from a group of hundreds of ticket holders for a few precious spots in a few desirable schools.

The most riveting moments in the film are those lottery pickings as power balls spin in the carousels, the numbers are read off, and the ticket holders watch and wait. Every face registers an arc of hope, anticipation, desperation, and resignation. Rarely, someone actually wins. When they do, they seem more relieved than thrilled. Those interludes are as anger inducing as they are heart wrenching. Those students and their parents have no other option than to let their hopes and dreams rest on a ball in a barrel.

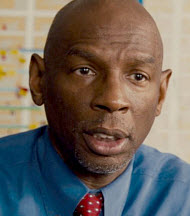

The film also tells the stories of teachers who, against great odds, continue to push for reforms. Geoffrey Canada, the president and CEO of Harlem Children’s Zone has been advancing the cause of education in poor neighborhoods for years. After receiving a Masters degree from the Harvard School of Education, he taught in the Boston Public School District. He says he discovered in his first three years that “I was a terrible teacher.”

From that understanding, he started a crusade that began with himself. He improved his skills by finding out what his own drawbacks were, looking for solutions to correct them, and applying those solutions to his classroom. He became a better teacher, and his students became better learners. He then did the same thing on a larger scale and has developed the Harlem Children’s Zone that gives students a plan to study by and to live by. That plan leaves no room for failure, but it has a safety net that lets the children know that there is always someone there to catch them if they fall off track, someone who cares and is devoted to them.

David Levin and Mike Feinberg taught in the Houston School system after they graduated from Ivy League colleges. They were disappointed in how their students were performing. They started using innovative methods to improve learning. Those methods grew into a program known as the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP). That program is now used in 82 schools (Geoffrey Canada has adopted it in his own school programs), and the schools in which it has been used have gone from poor performing to high performing ones. KIPP is another example of a school program that focuses directly on what is good for the students, not on what is easiest and most comfortable for the adults who are employed by the school system.

The adult who faces the greatest challenge in the film is Washington D.C. schools chancellor, Michelle Rhee. She had that job since 2007, and she resigned her position today, as I write this. Her resignation came on the heels of D.C. Mayor Adrian Felty’s failed reelection bid. His quest for a second term as Washington D.C.’s mayor failed, in no small part due to the campaign waged against him by the D.C. Teachers' Union, as well as the National Teachers’ Union. Rhee was the seventh D.C. Chancellor to hold the position in the last 10 years. The district is one of the poorest performing in the country, despite having more money spent per pupil than most other school districts.

Rhee initiated a number of reforms, the most radical of which was to close 23 underperforming schools. This caused outrage in several quarters, especially among members of the teachers’ unions. Despite the outcry, her reforms brought results. Test scores started to go up. Drop out rates went down. Rhee tried an even more radical approach to reform when she proposed raising teacher salary based on performance to as much as $120,000 per year if, in turn, she would have the authority to fire teachers who were not performing adequately in the D.C. schools. The teachers’ union refused to even vote on the proposal. They found it too threatening to their own status quo.

It would be easy to mark a villain here—way too easy. Sure, I’d love to point a finger at the Department of Education, the National Education Association, the American Federation of Teachers, and the Federation’s hapless President, Randi Weingarten. She is given the thankless task of trying to defend what Guggenheim has shown to be indefensible. The villains are not bad people. They’re not even apathetic. They are merely self-interested and self-seeking. But isn’t it that very egoism that lies at the root of all that goes wrong? When we turn our backs on God and on our neighbors, can it be a surprise that bad things result? The teachers’ unions are not comprised of evil people, but the unions' goals: keeping the status quo, protecting one’s own turf, striving for ease over excellence, are not altruistic ones. They seek their own good at the cost of those they serve. “Waiting for Superman” makes this point presciently as it brings to light the efforts and the sacrifices of those who do the real work and those who, as our neighbors, deserve our respect and support.

Violence: None / Profanity: None / Sex/Nudity: None

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

Moral rating: Excellent! / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Moral rating: Good / Moviemaking quality: 5

Our 10 year daughter was bored and left, but our teenage son watched it and was very puzzled as to why one of the young schoolgirl could not go to her graduation or the RUBBER room people being paid for what. I’m still not over that, so I understand where he is coming from. The system is laid out in this movie for you to understand who-what-where this beast is not going and the few people who are trying to make a change only to be hit with ROAD BLOCKS by the system itself and by ADULTS.

It will make you think about you as an ADULT (system is lacking mature adults) and how you view what is fair for CHILDREN and not just YOURS. Parents and the American citizens, should view this movie it is an eye opener. P.S. I though how strange it was that many of many consultant’s in this movie who report their finding to this beast get paid to tell us what the system is not doing, and this film is full of them… I need a new job

Moral rating: Good / Moviemaking quality: 4

My Ratings: Moral rating: Excellent! / Moviemaking quality: 4½